2020 build: Brave Puffin's steering

TL;DR

- Tilt compensated compass is a must

- Magnetic deviation is a thing

- Magnetic variation is also a thing

- Use PID controller for proper differential steering

Direction

To steer something, you need to know where you are going right that moment - a sense of direction. A magnetic compass is the best device to figure out which way you are facing.

I am often asked: “If the boat has a GPS, why does it also need a compass?”

Indeed, if you are a user of a GPS based map app while driving, you might think the GPS is all you need. Well, GPS only gives you a relatively accurate current position - but not a direction. For example, here are a few GPS fixes Brave Puffin got while just staying put on the sidewalk before one of the tests:

Which way was it facing?

From the position alone you don’t know which way (north, east, south or west) your vehicle is pointing to. Yes, if you are moving, you can try to calculate the direction by obtaining multiple GPS fixes, and derive a rough sense of direction from that, over time.

The problem is, an average GPS fix is accurate only to a few meters (see above). So computing a more or less precise direction of your movement will take lots of GPS fixes, and time. Let’s say a minute. During that minute the boat will experience the wind, the waves, etc. - and will likely be facing in a totally different direction. Averaging GPS fixes will be too slow to steer accurately*.

A magnetic compass is the best sensor for that job because it tells you which way you are facing relative to magnetic North, instantly. Gyroscopes can be helpful too - but they drift, so we won’t go there for now.

Tilt compensated compass

Here is my cheap, old school “analog” compass, intentionally not sitting flat on the table:

I can tell you that actual magnetic North was in a totally different direction. That happened because the compass needle got stuck in the wrong position, by hitting the bottom of the enclosure. It’s a crude analogy, but the point is: it is not easy to make your compass show accurate heading when it’s not laying flat, or is in constant motion. Which will obviously be the case on a boat.

A traditional solution for marine or airspace applications is to mount compass’ dial using the gimbal suspension, allowing the moving parts to pivot freely:

This achieves tilt compensation for accurate readings when the boat rolls and pitches. For robotic applications, we need something similar, but digital, and also supporting good tilt compensation.

Motion sensors

There are plenty of affordable digital motion sensors on the market, and many include both a compass (magnetomer) and accelerometer (gravity sensor). My favorite posts on the subject are Affordable 9 DoF Sensor Fusion and Simple and Effective Magnetometer Calibration by Kris Winer.

There is a lot of theory and engineering that goes into getting accurate tilt compensated readings even from off the shelve components using sensor fusion. I won’t go into all of the details, but only highlight the most interesting problems I had to sort out.

Initially, I tried MPU-9250 unit using Kris’ calibration and fusion code (https://github.com/kriswiner/MPU9250). It kind of worked, but was not accurate enough. Calibration was tricky, and the readings with large roll or pitch angles were off by as much as 30 degrees. I am pretty sure I was not doing something correctly.

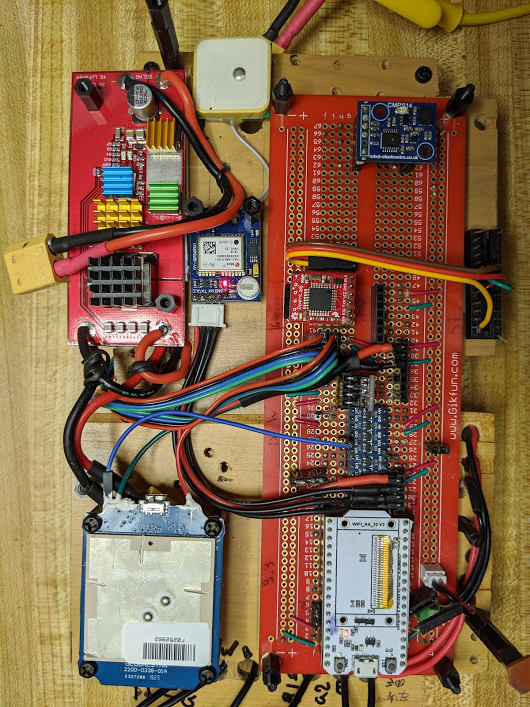

Researching the market, I found industrial grade components which would have probably worked much better, but they were expensive. Eventually, I stumbled on CMPS14. An excellent breakout board based on BNO080 package, providing tilt compensated compass features and calibration out of the box. Here it is, mounted on Puffin’s main board (top right):

I was very happy… Until discovering a few more challenges during testing.

Magnetic errors

A compass can be greatly influenced by the components of the boat itself. Specifically, any parts made of ferrous materials such as common steel, if placed too close to the compass, will affect its readings. The errors can be quite large. This effect is known as magnetic deviation. When implementing compass calibration, it is described and accounted for as hard and soft iron bias.

It is imperative to minimize the use of ferrous materials or place them as far as possible from the compass. Even a very small M3 bolt 8 cm away from compass can affect the reading. But, it is impossible to get rid of all of the local magnetic errors. Therefore, good, built-in compass calibration implementation is required, as the errors will be unique to the construction of each device.

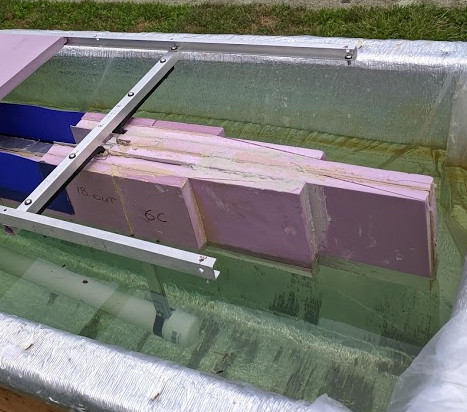

I knew some of this in advance, so Brave Puffin’s inner and outer frame, fasteners, as well as other metal components were built using aluminum and non ferrous steel:

However, what I did not know is that the electronic components (i.e. conductors, small parts and controllers) can also be the source of magnetic errors - I presume because of the minute amounts of ferrous materials. The worst part is that these magnetic errors grow over time when the device is on - the electronic components get magnetized**.

This problem got me stumped for several weeks in 2019, as the compass was giving accurate readings on a breadboard, outside of the enclosure. And then as I put everything together for the end to end testing, the magnetic errors popped up almost right away. As the boat went through many charge / discharge cycles in the test tank for a week, compass accuracy got progressively worse, and calibration became harder.

My solution was:

- Demagnetize the electronics and the board by using a commercial demagnetizing device, once

- Adjust the layout of the board and move the compass as far away from all other components as possible

- Move high current conductors away from the compass

CMPS14 - automatic calibration

CMPS14 comes with built-in compass calibration, which you can turn on / off programmatically. Its datasheet says:

To achieve background calibration the user just needs to turn the functionality on and perform the required simple movements

What I found is that to achieve high quality calibration, “simple movements” are not enough. I had to roll and pitch the boat at extreme angles, for up to 70 degrees, for about a minute or so.

My final approach was to perform good pre-launch calibration manually, but keep CMPS14’s background auto calibration off by default on restarts. And, to account for a very probably decalibration event during the mission, the boat continuously monitors compass calibration state, and will turn it on / off automatically. I hoped that constant wave motion in the open ocean will be enough to complete the process.

Magnetic variation

There is one more source of magnetic errors called magnetic declination, or magnetic variation. It is environmental in nature, and I plan on covering my approach to that problem in another post dedicated to navigation.

For now, let’s assume the boat knows its precise location (via GPS), its precise current heading (via compass) and it also knows where it needs to go - the next waypoint. I.e. at any given time, the boat can calculate the delta between its current heading and the desired course to the target.

How do we convert that delta (in degrees) to the input of two motors, to achieve optimal differential steering?

PID controller

Let’s say the boat is currently pointing to 0 degrees i.e. directly north, but its next waypoint lays to the east, on a 90 degree course. How much relative power should we give to the left vs. right motor?

Since this requires a sharp right turn, one approach is to simply give the left motor extra power, directly proportional to the delta. Say, 90% more power. As the boat starts turning, the delta will decrease, so we decrease the extra power on the left motor proportionally to avoid overshooting. For example, 45% more power for a 45 degree turn, 10% for 10, and so on.

This approach will work in a bathtub, but not in the real world.

In any real conditions there will always be external forces - the wind, the waves, the currents - which will push on the boat. As the delta gets smaller, and our naive algorithm gives the left motor less and less extra power, it will never be able to actually nail the course.

Brave Puffin uses PID controller to achieve optimal steering, which is a common approach in the industrial control systems. PID algorithm adjusts inputs by relying on a feedback loop, and factors in time as a component to balance the speed of corrections vs. overshoots.

There are a few open source PID controller libraries targeting microcontrollers. However, my MCU in 2019 was lacking the storage and RAM to accommodate the extra code, so I implemented my own, very simple PID controller.

The standard algorithm uses several terms, each with own coefficient (constant), which will be specific to each device or system. The tuning constants need to be selected during a tuning process.

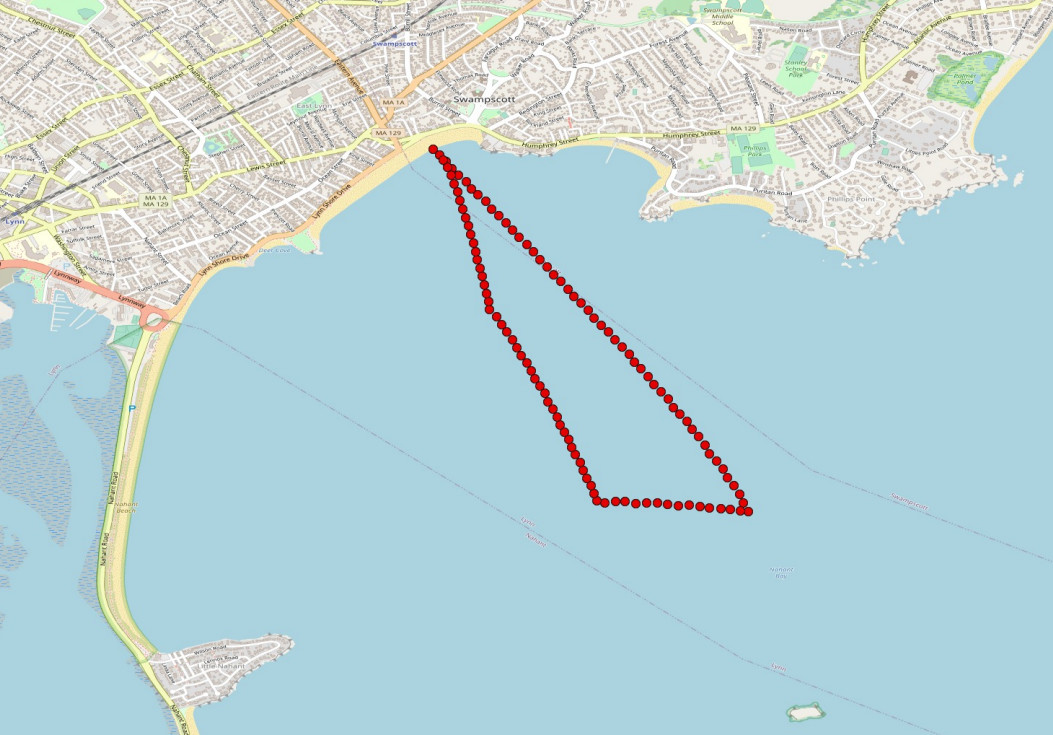

Here is Brave Puffin during PID tuning process - you can see large overshoots and oscillations at the beginning:

And here it is after completing the PID tuning, sticking to the desired course straight ahead:

Results

It worked out well, I think. During testing, the boat’s steering could handle fresh breeze and small ocean waves easily, sticking to its route:

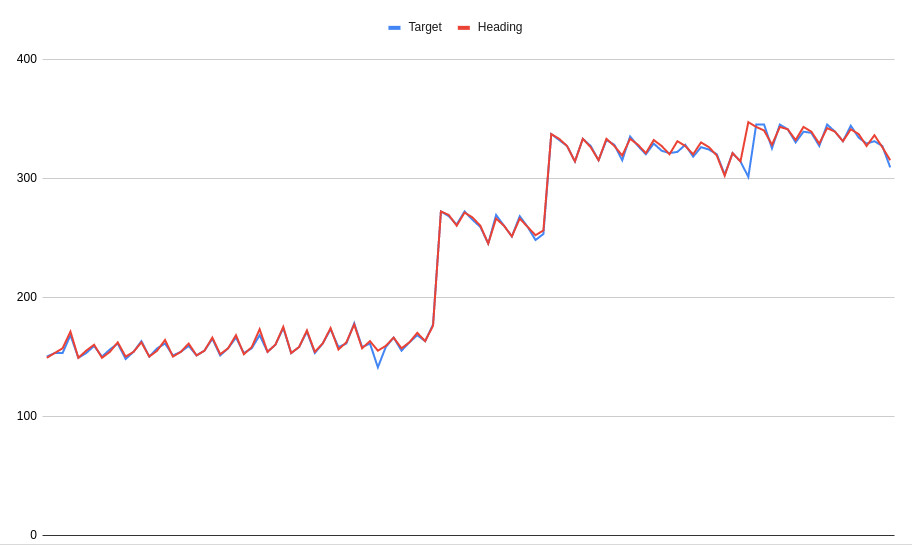

Here is the telemetry data from the same test run. Y axis is degrees, blue line is desired course to target, and red line is boat’s current heading.

Ignore the seesaw nature of the target course (navigation feature) for now. You can see that by and large the red line follows the blue line closely, which means Puffin was staying on the desired course for most of the run.

If only that would be also true during the actual 2020 race attempt! :)

* That said, I did want to experiment with GPS averaging approach as a backup for compass based steering. It should be possible to rely on gyros for real time steering, and use GPS for slow, over time course corrections. It could work OK in the open ocean over the long run, the trouble is - it’s hard to test something like that. Maybe next time.

** I am not an electric engineer though - this is my best theory for what I was observing.